Siomara Alonso flipped through Reader’s Digest one humid May night in 2004. The 50-year-old natural beauty with caramel hair sat alone on a suburban back patio.

She couldn’t see the stars or the sky.

She longed for the space of her mountain farm in Venezuela and the high-ceilinged home she had left behind. Suddenly her cousin Yoli shouted from inside the cramped three-bedroom Kendall house: “Hurry! Come quick!” Siomara bolted to the living room, where she had been crashing on a sofa bed since late February.

The 11:00 news flashed to the South American home where she and her husband had lived for two decades. Dozens of strangers appeared, trashing the couple’s handmade shutters with hammers and tearing down the oak blinds inside. The piano clanged off-key as it tumbled down a hill. Books burned in the yard.

A broadcaster explained that neighbors were enraged that Robert Alonso — Siomara’s husband — had been training terrorists. A few days before, the government had arrested more than 70 Colombians on and near the property. They were said to be paramilitaries plotting the overthrow or assassination of President Hugo Chávez.

From the couch, Yoli hurled curses at the tiny old TV set. Siomara stood silently. Shocked and numb, they watched as people in ratty clothes, some missing teeth, dumped the silk and cotton contents of Siomara’s top dresser drawer onto the brown, sun-dried Spanish tile floor. They stomped on her pink and white underwear. Those were not her neighbors.

She sobbed over what her life had become. Robert was in hiding. How would she support her two sons, ages nine and 11, who were sleeping in a spare room nearby? Home as she knew it was gone.

These days Robert and Siomara live in a secret Kendall location. He is a Venezuelan outlaw accused of urging his countrymen by radio, newspaper, and the Internet to hit the streets and cause anarchy.

Robert dubs the plan that caused him to flee his homeland La Guarimba, and says it’s nonviolent. But the last time he made his pitch for revolt — in 2004 — at least 13 people were killed and more than 100 were wounded in clashes. “If you don’t follow the instructions, it’s not my fault…. When you commit yourself to something, you have to quemar los barcos, burn the ships. There’s no way out,” says the 57-year-old with a shock of white hair and an ample belly. “We’re at war.”

Robert and Siomara (“my friends call me Siomi”) Alonso are both Cuban by birth. She comes from Havana, the only child of an insurance broker and stay-at-home mother. Her family left the island in August 1960, a year after Fidel Castro’s forces overthrew President Fulgencio Batista’s regime. Her father arranged a job transfer to Caracas, and for Siomi, Cuba became nostalgia flashes — lizards in the back yard, rocking chairs, and the smells of her grandmother’s home. She’s unlike Robert, who is plagued by the unrelenting gnaw of Cuban politics.

Roberto Alonso Bustillo was born in August 1950 in the tranquil province of Cienfuegos, where, he says, the “smell of the sea filled our lungs every morning, and one car, if even, passed every half-hour.” He was a squirrelly, mischievous kid who favored horseback riding, fishing, and playing cowboys and Indians. One time the boy rubbed a piece of candy in some leaves that made it spicy-hot, then rewrapped it, and gave the sweet to a friend.

On January 3, 1959, the eight-year-old reached out to Fidel Castro during a parade. He felt hopeful about the triumph of the revolution. A couple of years later, Robert remembers, he was pedaling up to his family’s upper-middle-class home. (They belonged to a yacht club nearby.) There he saw his parents giving away their furniture, clothes, and TV sets to friends. He says his father, Ricardo, took a baseball bat to their chandelier. They didn’t want Castro’s government to inherit their possessions.

That night Ricardo, his wife Conchita, their three children, and a Pekingese dog named Chato piled into a borrowed car and left the empty home. They headed for Havana. There a veterinarian friend forged documents showing Chato was a mutt. (Castro wouldn’t let anything valuable leave the country, including pups, Robert says.) Three days later, on Robert’s 11th birthday, the family departed for Caracas with 13 suitcases aboard an old Spanish ship.

People gathered at the docks and shouted, “Gusanos! Imperialistas!” But soon those chants drifted unheard into the wind. During the trip, Conchita knelt before Robert and explained his parents were “counterrevolutionaries.” She hugged him and said Fidel was a bad man. “That morning of the 24th of August 1961, I became Cuban,” he would later write in an essay.

At the first pensión, or boarding house, in Venezuela, the family shared a bathroom with prostitutes, Robert recalls. (Robert, who has a knack for storytelling, claims they drifted to 10 pensiones that year; his brother, Ricardo Jr., and sister, Maria Conchita, now a famous actress, peg it at two or three.)

Soon Ricardo found a gig selling used cars. Robert and his brother passed out flyers at a stoplight.

Next their father set up a rattan-importing business. Ricardo Jr. immersed himself in student politics, but Robert wasn’t interested. When Robert was around 15 years old, his parents sent him to the United States, where he lived with family friends on a farm in Washington State. There he learned to chop wood, tend pastures, and make taffy.

His sister later joined him. Once they performed together in a talent show. She sang and Robert, an aspiring musician who resembled Elvis, accompanied her on a Spanish guitar. After graduating from high school, he studied business in Spokane. In 1972 he traveled to Munich to study TV and film production and then to Scotland for communications classes.

The following year, 23-year-old Robert returned to Venezuela, where he met Siomi, who was five years younger. Their families belonged to a Cuban social club in Caracas and pushed them together. When Siomi’s cousin invited her to an Engelbert Humperdinck concert, she needed a date. Who would want to go to that? she thought. Robert was the answer.

They didn’t talk politics. She was charmed by his compliments and jokes. They ended the night with a kiss. The next morning a bouquet of white daisies shaped as a poodle arrived at her door. Ten minutes later, Robert showed up. Seven months after that, they married. At the time, he ran a mop rental company that his father had helped him start.

But unbeknownst to his new wife, by the early Seventies, Robert had become active in la lucha against Castro. He says he collaborated with the CIA and other U.S. agencies. (Asked to confirm Alonso’s collaboration, CIA spokesman George Little responds, “We do not, as a rule, comment on these kinds of allegations.”)

Robert’s answers get murky when he is asked specifics about his work. “It’s not like it seems in the movies. There are things one can’t say.”

Like some of the most radical exiles, in 1976 he joined the U.S. and South African soldiers in Angola, fighting Marxist-Leninist forces propped up by Castro in a civil war. Robert saw it as a chance to confront the dictator. Cuban deployments reached tens of thousands.

To Siomi, he explained his lengthy absences as “business trips” to places like Cleveland, where the mop company had an office. In Angola, he says, he interrogated Cuban deserters to see if their motivations were legit. “It was a party of collaboration,” he says. “And if they wanted to come to the party, they had to bring a bottle of wine or liquor, in terms of information.”

His gun of choice was a Colt .38 pistol. When pushed for details about how he used it, he says only: “The most interesting parts I can’t talk about.”

In his daily life, Robert became a family man. The couple’s first child, Carolina, was born in 1976. Siomi recalls Robert trying to snatch the baby from the hospital nursery just to hold her longer. At home he plopped her on his belly to watch Zorro.

Their second child, Carlos, came in 1979. Robert started a TV production company in 1982 and launched a version of That’s Incredible! in Venezuela. He’s also a prolific writer, having penned books like Memorias de Cienfuegos (1983) and Los Generales de Cuba (1985). He talks fast, but writing seems to give his prodigious thoughts and words a chance to catch up.

The “business trips,” he says, took him to Afghanistan, Bolivia, Grenada, Guyana, Zimbabwe, the United States, and France. But the secrets wore on his marriage. He typically didn’t call home when he was on the road. Finally, in 1986, nearing divorce, Robert confessed to Siomi.

“I was angry at first because I thought he was having an affair,” she says. “Then I was furious because I wanted to know more. He expects a lot of understanding and patience, even though I would enjoy knowing a lot of things, I respect his wishes.”

Responds Robert: “The last person you tell is your wife. Sometimes she feels left out like the guayabera.”

Around 1988, Robert halted the trips as the Cold War wound down. The couple bought an old coffee plantation about an hour outside Caracas, where daisies grew wild. They christened it Daktari for the Sixties TV series in Africa and retreated to a home they built there the next year. “We decided to separate from the world and lived like monks.”

The home grew to four stories. Then came a small swimming pool overlooking a jungle dotted with clouds. Later there was a piano bar, a vast library, and a stock of animals that included Colombian paso fino horses (he made money selling their sperm), German shepherds, and ostriches. Finally, there was a Japanese garden with a koi pond.

Baby Alejandro arrived in 1992, followed by Eduardo in 1994.

In 1998, when Hugo Chávez ran for president on a promise to stamp out poverty, Robert warned friends about voting for the former paratrooper turned caudillo. But after Chávez was elected, Robert didn’t immediately take action. He absorbed himself in writing a novel about Cuba and stayed relatively quiet until a two-month general strike erupted in December 2002.

Then he began penning letters to newspapers and friends. He also collected tens of thousands of e-mail addresses to spread his theory about derailing the Venezuelan president. “You can say his midlife crisis hit him in his political genes,” Siomi says. “He was passionate about me and the children, but you could tell his mind was kidnapped…. He has become a different man since he has gotten himself into this craziness.”

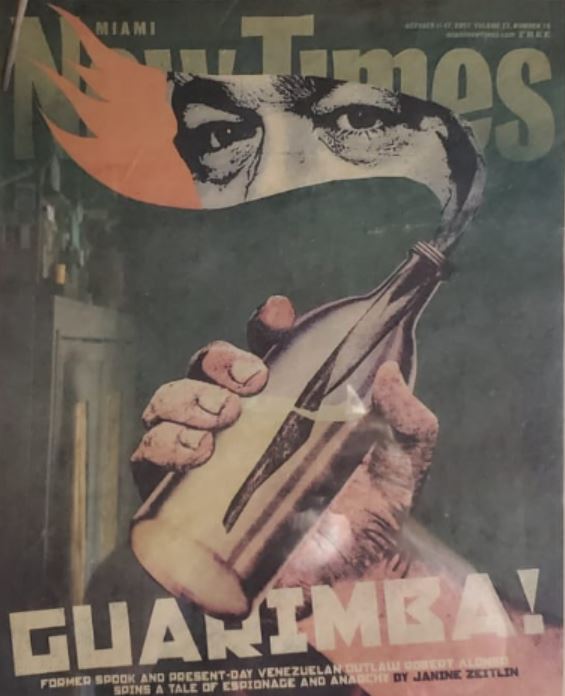

Flaming heaps of dead trees, tires, and trash blocked the streets of Caracas and other cities at the end of February and early March 2004. Molotov cocktails rocketed toward National Guard soldiers. Demonstrators swaddled their faces with Venezuelan flags to ward off tear gas. Traffic was clogged, banks were closed, and garbage collection was thwarted. Thousands couldn’t get to work. And while ashes smoldered in neighborhoods that looked like war zones, dozens of protesters nursed wounds from gunshots. At least 13 people in the streets during what came to be known the Guarimba — after a kids’ game — were dead. The Venezuelan government would issue a U.S. press statement blaming the “Guarimba plan” for “systematic acts of violent and disruptive civil disobedience designed to protest President Chávez, generate headlines, and create fear among civil society. The plan’s chief architect, a Cuban exile named Robert Alonso, is currently sought by Venezuelan authorities.” Chávez even appeared on national television to call Alonso “one of the ideologists of the so-called Operation Guarimba.”

The real genesis for the plan, Alonso says, is an 88-page booklet, From Dictatorship to Democracy, written in 1993 by former Harvard researcher Gene Sharp. It is a self-help work of sorts on how to use nonviolent, active resistance to overthrow a dictator. The booklet has been printed in 27 languages, cited by opponents credited with unseating Slobodan Milosevic in Serbia and banned in Burma. According to the now-79-year-old Sharp, strong and strategic nonviolent resistance from the people can work to paralyze society and cause a dictatorship to crumble.

Sharp has spoken to Alonso but declined to comment about the Guarimba, saying he doesn’t know its architect or the plan well enough. He says the Albert Einstein Institution, a small Boston-based think tank that he runs, doesn’t offer advice to budding revolutionaries. “We don’t tell people what they do,” he says. “If they find our work relevant, well, here it is.”

Alonso says he first read Sharp’s book on a friend’s recommendation after 19 Venezuelans were killed during an anti-government march on April 11, 2002. The next day Chávez was ousted from office. The president returned to power two days later, when an interim leader stepped down after losing military support and street protests erupted calling for Chávez’s return.

It was then that Alonso accepted Sharp as his personal savior. Soon Alonso and some other activists began hatching plans to permanently end Chávez’s reign. They discussed blocking streets in front of their homes, where they could retreat to if needed. At a meeting, Alonso recalls, one of the conspirators chipped in, “It’s like the guarimba.” Alonso explains: The term describes a traditional game in which children try to pass from one circle to another without getting caught by a person who is “it.”

Chávez was “it.” Those who joined the Guarimba would be like kids trying to dodge him.

In December 2002, Alonso began feverishly e-mailing alertas criticizing Chávez and describing future action. His contact list swelled to more than two million e-mail addresses. The Guarimba was a frequent topic. He spoke at neighborhood meetings and became known as “el padre de La Guarimba.” In a May 2003 essay, he wrote, “The only thing that this plan requires is that EVERYONE head out into the streets IN FRONT OF OUR HOMES and remain there…. La Guarimba is total anarchy. Everyone does what they want, depending on their level of frustration.”

There were three golden rules: (1) Block the street in front of your home. (2) Don’t go any farther than the front of your home. (3) Don’t confront the enemy. Alonso urged his followers to be prepared for at least one month “of battle” by stowing food and water in advance.

After more than a year of alertas, in late February 2004, he delivered cryptic news to Siomi and their two younger sons at Daktari: “You will be safer in Miami,” he said. “I cannot afford to concentrate on what I have to do and be worried about you.”

She argued against leaving and pressed for details. His answers were enigmatic. She suspected the Guarimba. They divorced — to cut legal ties. He bought them plane tickets and then vanished for two days.

Before their Friday flight, Alonso showed up Thursday night at Siomi’s parents’ home in Caracas to make sure she and the kids had left the farm. The couple and their older daughter, Carolina, embraced in the street. Siomi made the sign of the cross on his forehead before kissing him goodbye: “Be careful. Remember that you have a family that loves you.”

With two suitcases and a PlayStation, Siomi and the boys departed for MIA. On February 27, they landed in Miami and headed to her uncle’s three-bedroom Kendall home.

Then the Guarimba exploded. Alonso says it began after an anti-Chávez leader (whom he now calls a traitor) went on television and told people to block the streets. He says he had been working with others to spark the Guarimba on March 5 and cap it with a military ouster two days later.

Thousands flooded Caracas’s streets, many demanding a recall vote of President Chávez. National Guard troops shot tear gas canisters and rubber bullets at protesters, who blocked entrances to Caracas neighborhoods. They pitched rocks and gasoline bombs back at forces that rolled through streets in armored tanks. Two protesters were shot dead on barricaded streets on February 29.

Two days later, as expected by the opposition, the National Elections Council rejected nearly half the signatures on a petition demanding a recall. As the council claimed fraud, riots raged in Caracas, its suburbs, and at least 10 other cities. An anti-Chávez activist was shot in western Venezuela. A young opposition protester was apparently shot by a sniper. An estimated 300 people were arrested, some claiming torture. Amid the chaos, Alonso says, he took to the Caracas streets to try to quell violence. Though he went on radio to urge people to continue the Guarimba, protests slowed the first week of March, when the elections council and some opposition leaders agreed to negotiate about the signatures.

Despite the melee, Alonso declared the Guarimba a total success. In a video he made about the protest, “Amazing Grace” plays over footage of shirtless men with bleeding wounds and demonstrators cowering before military police. He encourages people to use their cars to block the streets: “Next time we will triumph!”

Then he was tipped off that the police were coming for him. Toting $2000 in cash, he went into hiding.

When Robert Alonso became a fugitive, one of his first stops was a friend’s house. But the man’s wife became so nervous she shook uncontrollably, and the ice almost fell from her whiskey on the rocks. So he considered other options.

His story from the underground days that followed sounds as if it were cribbed from an espionage thriller. (In fact Daktari and its owner appear in a 2006 spy novel, The Beast Must Die, by best-selling French author Gérard de Villiers.) One day he would board a bus bound for a Venezuelan coast and grab some shut-eye during the voyage. At the final stop, he’d board in the opposite direction. And then he’d repeat.

On layovers, Alonso says, he ducked into funeral homes and blended with grieving families. He recalls napping in beds for sleep-deprived mourners and gulping down complimentary hot chocolate. In public he wore sunglasses and contact lenses to mask his pupils and carried a walking stick so he’d seem blind.

At some point in April 2004, he met with other activists calling themselves the “Brigade Daktari.” (A Venezuelan flag hangs on his home office wall with about 50 signatures from this mysterious meeting.) Then he left for Colombia. Carrying a GPS, Alonso says, he navigated the jungle between the two countries and then hopped a bus to Bogotá. He took a plane to Miami in late April.

He lived apart from Siomi and their two young sons in Kendall so they’d be safe. His fugitive odyssey continued. On Mother’s Day, May 9, he learned Chávez had announced a victory in “the fight against terrorism.” Seventy-seven alleged paramilitaries had been arrested and accused of a plot to overthrow Chávez’s government. In a Sunday address the Venezuelan president said, “All these arrests were made at the farm of a citizen of Cuban origin — of the Cubans known as worms, the anti-Fidel, the Cuban counterrevolution, which moves through Central America, Miami, North America, and South America — whose name is Robert Alonso, nicknamed ‘El Coronel.'”

Chávez applauded the three months of intelligence work by the government’s police for cracking the operation that yielded Colombians dressed in Venezuelan military uniforms. Alonso denies being capable of carrying out such a plot, saying he was gone long by then. “Am I Superman or 007?” he asks.

When Maria Conchita Alonso heard the Venezuelan government link her bother to terrorism, the now-50-year-old Hollywood actress thought, “Oh please. Terrorists are people who don’t care about anybody. Terrorists are killers that are not lovers of freedom and democracy and equality among people. [This is not] my brother.”

At the time, José Prado, general manager of TeleMiami, was vacationing in Caracas. He recalls seeing news of the case clog TV. “They presented his army, but the army didn’t have shoes,” he says. “That was a joke.” A day or so later, he contends, armed police stormed a plane he and some others had chartered to a nearby island. “The pilot said they were looking for Robert Alonso.”

By May 17, a Venezuelan government news release reported that more than 100 Colombian paramilitaries had been captured in connection with the Daktari plot. In another strange twist, a dead body had been found.

The men went on trial in October 2005. One Colombian suspect said he accepted work as a farmhand near Bogotá, but then was shuttled to Daktari, where Alonso greeted him. The man claimed that while he stayed on the property, he and the others did military exercises with sticks and were shown videos of armed men assaulting buses.

But apart from a pistol found on one man, no weapons were seized, and some people questioned whether the government had crafted the plot. A detainee shouted “sham” in court. Eventually, only 27 of the 100-plus Colombians were convicted, and three Venezuelan officers were sentenced, for conspiring. A month and a half ago, Chávez freed the convicted Colombians. It was a way to promote peace within the neighboring nation, he said.

As to the alleged paramilitaries, Alonso and his wife say the Colombians were likely sent to his property as payback for the e-mail alerts urging chaos to overthrow Chávez. “If it was a real crime scene, why would they let those people in our home to destroy the evidence?” Siomi says, referring to the day her underwear starred on the news.

In October 2004, Venezuela demanded Alonso’s extradition after his name popped up in a Miami newspaper report. Alonso says his family’s address was later posted online. They fled to Washington State, where he had spent time on a farm as a teen. He recalls the shabby cabin where they stayed in Onalaska, a town of a few thousand. When he told a gas station attendant he was from Venezuela, the response was “Where’s that?” Alonso’s reply: “Oh, it’s a few miles from the Mississippi, just across the river.”

The family returned to Miami, and after consulting a lawyer and quashing the extradition, the Alonsos were granted legal residence in 2005. Their Cuban nationality helped speed up the process. They rented a tiny efficiency. “The kids played PlayStation five inches from where their father was writing things against Chávez,” Siomi says.

Siomi’s saintly patience with her husband’s world of spies and freedom fighters, contras and communists, traitors and good Americans seems endless and absolute. She doesn’t blame him for losing Daktari: “[His political work is] his passion. I guess he feels that’s his calling. But it drains him. It doesn’t allow him to lead a normal life.”

For the next year or so, Alonso took various jobs, such as driving a private ambulance and shuttling elderly people to medical appointments. In 2006 he began producing and posting online videos under the tag Guarimba TV. Soon he branched out to Internet radio. In early August he was hired as editor of Venezuela Sin Mordaza (“without a gag”). He’s wrapping up another book. And on radio station La Cadena Azul 1550 AM, he cohosts La Voz de la Resistencia, a Saturday-morning show dedicated to promoting freedom in Cuba, Venezuela, and Nicaragua.

What does he talk about? On an Internet radio show one afternoon in early September, he said, “I spend 25 hours a day in Miami analyzing Venezuela. The country is lost. We must get it back.”

In a Don Pan bakery in Miami’s suburbs, Robert Alonso plots the next Guarimba. It’s a mid-September day, and he’s peering over his gold wire glasses at a recent edition of Venezuela Sin Mordaza.

Some highlights: “A Communist, Me?” “Dictionary of International Castro-Stalinism,” a poem by José Marti, a piece about Sharp’s book, and “The Mission of This Traitor,” which describes the opposition leader who urged Venezuelans to stop the 2004 Guarimba and negotiate with the government.

Other newspapers and books clutter the faux-marble table where he sits as nearby customers mull over chatos, empanadas, and strawberry-topped cakes in smudged glass cases.

Alonso looks like a retiree who stopped by for an afternoon cafecito. He’s wearing blue sweatpants, tan sandals, and a turquoise T-shirt. The clamor from the espresso machine and blenders fills the room as a man in a button-down shirt carrying a briefcase strides through the bakery doors and beelines for the table. He silently drops a manila folder before Alonso.

The mystery man is Marlon Gutiérrez, a 45-year-old former Nicaraguan Contra. Alonso takes some papers from the folder and looks them over. They are bylaws for their new group, Fundación Interamericana por la Democracia, which will organize Guarimba resistance movements in Nicaragua, Cuba, and Venezuela.

“Robert is Chávez’s strongest adversary,” Gutiérrez says.

“This is a historic moment,” says Alonso, signing the papers. “With this, we take down the tyrants.”

They discuss recent developments. A high-level Venezuelan politico mentioned the Guarimba. An anti-Guarimba law was passed in Nicaragua. Chávez in a recent speech referred to Sharp and a golpe suave — a gentle coup — being planned from Miami. Alonso delights in needling the Venezuelan leader. “Chávez says, ‘We have been watching them in Miami,'” he says in a gruff voice. Then he pumps his finger in the air and breaks into snickers. “And I say, I’m watching you from there.”

These days the former fugitive scrapes by as editor of Venezuela Sin Mordaza. Siomi works as a clerk at a Coral Gables investment bank. Together they earn about $1500 a week. Friends have loaned them money for clothes. The Alonsos’ sparse three-bedroom apartment contains used furniture from street corners in Coral Gables, and bookshelves are actually stacked plastic crates. (Alonso offers his humble abode as proof he’s not being paid by the CIA.)

A Venezuelan mortgage broker, Edgard Paredes, launched Venezuela Sin Mordaza July 24, using about $20,000 of his own money. The paper has swollen from 20 to 28 pages, and Paredes claims it’s now self-sustaining. Along with radical anti-communist stories are breezy entertainment features like “The Prince of Salsa” and sports stories, such as one about car racing. Advertisers include a vegetarian restaurant, car dealers, and travel agencies.

Paredes is a 49-year-old former radio broadcaster who moved to the United States from Caracas in 1998. He started the newspaper to fend off Chávez’s power grab: “We have to move from the defensive to the offensive,” he says. “No boxer ever wins defending himself.”

Paredes and the first editor, Ricardo Guanipa, quickly parted ways because the publisher wanted a tougher anti-Chávez stance. Not a problem for Alonso. (One headline from when he first took over: “A Country on the Defensive Will Never Topple a Tyrant!”)

And the paper prints unapologetic anti-Chávez and anti-Castro cartoons. One shows Chávez in a straitjacket with the heading “Looking for an Escaped Loony!” Another includes Castro struggling under a mound of microphones and the tag Freedom of the Press and Expression. Miami’s Cuban exile community has supported the Venezuelan opposition.

The September 13 edition of the paper featured a front-page graphic titled “Resistance Cells.” It exhorted each Chávez opponent to contact five others; doing so would create an organized resistance. A quote accompanies the graphic: “Only God is more powerful than people united in a civic, active, general enduring revolt.”

Alonso contends the paper has an impact. One week after the graphic in Venezuela Sin Mordaza was published, he claims, 3000 cells including 15,000 people had formed in Venezuela. Asked how he knows that, he says people report back from Venezuela. He says he’s working with others to form cells in Nicaragua and Cuba.

While her brother calls for a revolt from Miami, Maria Conchita Alonso criticizes Chávez in other ways. The actress, who has played Eva Longoria’s character’s mother on Desperate Housewives, plans to produce and act in a film: Two Minutes of Hate, based on the April 11, 2002 events in Venezuela — which set the stage for the 2004 Guarimba. “What [Chávez] wants is to have another Cuba there,” says Maria Alonso, who moved from Venezuela to Hollywood when she was in her mid-twenties.

The former Miss Venezuela believes it’s her civic duty to oppose Chávez: “Otherwise I’m an accomplice.”

Speaking from her home in Beverly Hills, she says she thinks the Guarimba could be a solution. “You’re not telling anyone to go be aggressive and kill,” she says, her voice wavering. “Venezuelans have to help themselves. We all have to do something.”